When You Cut into the Present the Future Leaks Out: William S. Burroughs' Anthropological Imagination

I: Yagé Is Spacetime Travel

“I read about a drug called yage, used by Indians in the headwaters of the Amazon.”

On a cool June night in 1953, Bill Burroughs sat quietly in the darkness of a farmhouse on the edge of the Peruvian rainforest and realized that the secret to spacetime travel, which for a split second he had seen with perfect clarity, was slipping away from him. As he drank carefully from the cup of yagé (a powerful psychedelic also known as ayahuasca) the curandero passed around the small group of Shipibo men and women, the walls began to vibrate as if the room were flying at high speed. Everything around him stirred with the peculiar writhing life of a Van Gogh painting. The posts of the house took on the shape of the Easter Island statues, and Burroughs saw them as archaic grinning faces, like Polynesian masks, indigo splotched with gold. Everything is blue and beautiful, it’s a blue drug and you only take it at night, he thought. Suddenly he was possessed by the indescribable blue substance, which transported him across the ocean in a vast, timeless migration of outrigger canoes towards the Pacific Islands, and then on incredible journeys through jungles and deserts and mountains and down into valleys where his body withered and died, plants growing out of his cock and armies of crustaceans hatching inside of him, breaking the shell of his body. The room shook as he hurled through time and space. His body began to mutate into different forms, men, women, but also new genders and races yet unconceived and unborn, combinations not yet fully realized. Burroughs was flooded with sexual desire, but, rather uncharacteristically, for women. It was the most powerful drug he had ever experienced. Bill felt the bottomless depression he had been in for almost two years begin to lift, and a sense of serenity he would have been happy to experience indefinitely. Yagé is it, Bill thought. It is the drug that really does what others are supposed to do.

Today, ayahuasca tourism and treatment for depression, post-traumatic stress, and addiction are a growing industry. Thousands of articles and books have been written about its chemistry, effects on human physiology, cultural history, and the social and environmental problems it has caused for Amazonian indigenous groups like the Shipibo-Konibo and the Xetebo. You can book a week-long yagé retreat with a “certified shaman” or purchase the ingredients on your phone in under an hour. But in 1953, only a handful of travelers and scientists in the United States had even heard of the esoteric drug, and no one knew the secret to making it.

One of those people was Burroughs, who, out of desperation and going on little more than a hunch, decided that he would find out for himself. Long before his literary fame, in the early 1950s Burroughs became the first American (and probably the first Westerner) to travel to Ecuador, Columbia, and Peru with the express purpose of treating his mental illness and addiction to opiates with ayahuasca. Although it was well-understood by botanists working in South America that the main ingredient in yagé was pounds and pounds of boiled caapi vine (Banisteriopsis caapi, which has a very mild psychoactive effect on its own, similar to cannabis), scientists had yet to correctly identify the “secret” ingredient or ingredients that resulted in the full four to six hour trance-like experience. In the course of his research for a 2006 revised edition of Burroughs’ book The Yage Letters (1963), writer Oliver Harris discovered that Burroughs was also probably the first Westerner to correctly identify the leaves of the chacruna plant (the Quechua word for Psychotria viridis, which contains the hallucinogen DMT) as the secret ingredient that makes yagé so incredibly powerful. This work was overshadowed by Burroughs’ novels, particularly the book he is synonymous with, Naked Lunch, which cemented his mythology as the junky murderer who fled to Africa to get fucked by men, take illegal drugs, and write an obscene novel that seemed to become part of the literary canon as much for its audacious, kaleidoscopic construction as for its timeless ability to shock the Middle America that spawned its monstrous author.

The story of Bill’s yagé quest and his stints in graduate school for anthropology—before he was a writer, and before things got irrevocably dark—hints at an alternate universe Bill Burroughs, the person he might have been had things gone differently. It shows a young man whose imagination was fueled by a fascination with other cultural norms outside of his own, who was full of fantasies of becoming a professional archaeologist and moving to South America with his family to study the ancient Maya. It also helps to explain why so many people (myself included) encountered Burroughs’ novels accidentally mixed in with the books in the Cultural Studies/Anthropology sections of used bookstores, novels with passages that a first glance resembled deranged ethnographic field reports by a colonial authority who had clearly lost his mind.

II: There Are No Accidents in the World of Magic

“I found the temple in ruins the stellae broken and no one knew any more how to use the calendar.”

Burroughs’ picaresque heroes often find themselves in perilous situations where their command of ancient religious magic or indigenous knowledge is ultimately what saves them. Flip through any of his books and in a few pages you are likely to encounter shamans and brujos, Mayan priests and ancient codices, Easter Island Moai and Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chimu funeral urns and Chancay necropolis mummies, curare poison darts and sweet potato diffusion, corn gods and Aztec calendars, bouts with koro or kuru or candiru or some other horrific exotic malady, human sacrifice and other strange rites, expeditions upriver to make contact with the Ingano or the Shipibo or perhaps the Jívaro this time. While his work is patently not anthropology, it’s pretty unquestionably anthropological.

Anthropology appealed to Burroughs because it’s the only scientific discipline to take the social function of magic seriously, and the only discipline that goes out of its way to highlight cultures in which magic serves important, occasionally indispensable, functions.[1] He had been obsessed with magic from as early as he could remember. “Since early youth I had been searching for some secret, some key by which I could gain access to basic knowledge and answer some of the fundamental questions.” The search for a missing key was cultivated by Bill’s mother, Laura Lee Burroughs, who, like many wealthy[2], upper-class Victorians was fascinated by spirits and magic. Throughout Bill’s childhood, Laura, who claimed to have psychic powers, was preoccupied with the fashionable trappings of Spiritualism: auras, table-tapping, crystal balls, and even ectoplasm (which makes some notable appearances in Naked Lunch). Thus growing up little Bill was steeped in a very safe, very well-to-do version of the occult.

Some of Burroughs’ earliest memories were of supernatural experiences that had a profound impact on him. His most vivid memory was from when Bill was about four. He was playing in a grove of trees when he saw a delicate green reindeer, about the size of a cat, “clear and precise in the late afternoon sunlight as if seen through a telescope.”

“Later, when I studied anthropology at Harvard, I learned that this was a totem animal vision and knew that I could never kill a deer.” This is pretty typical of Bill’s use of anthropology in his personal life. Per se, he’s not interested in the concept of totemism (the veneration of a plant or animal that symbolizes a cultural group). He’s interested in the details, the magical “recipe.” What Burroughs takes away is generally out of context and always quite literal: his totem animal is the deer, and thus he must never harm a deer—he’s not at all concerned with how it functions in its original cultural context, or fits into social theory.

Bill was, earnestly I think, convinced that magic is a fundamental driving force in the universe. In The Spiritual Imagination of the Beats, writer David Calonne argues that Burroughs was a spiritual magpie, creating his own religion by blending elements borrowed from an eclectic mix of mythologies and world religions. (His pantheon incorporated ancient Egyptian and Mayan cosmologies, Tibetan Buddhism, obscure religions such as Manichaeism, Isma'ilism, and Zoroastrianism, among other isms, and newer, culty movements such as Scientology and the sham shamanism of the fabulist Carlos Castaneda). This blending of religions is what anthropologists refer to as syncretism, a mosaic of different faiths used to create a new tradition (the African diaspora religion of Vodou is the classic ethnographic example). A voracious reader, Bill was forever adding to his syncretic religion, creating his strangely anachronistic “mythology for the space age.”

III: Great Chain of Being Vibes

“The essence of White Supremacy is this: they are people who want to keep things as they are. That their children's children's children might be a different color is something very alarming to them—in short they are committed to the maintenance of the static image.”

Burroughs minored in anthropology at Harvard in the early 1930s but was not an avid student, preferring English literature and anthropology-adjacent topics. Witchcraft was a favorite, spurred by his English professor George Lyman Kittredge, author of Witchcraft in Old and New England, as were Buddhism, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, yoga, and astrology. He read some of the popular ethnographies like Coming of Age in Samoa produced by the fabled Columbia University Department of Anthropology, at that time led by Franz Boas, founder of American anthropology, and Margaret Mead, then its most famous practitioner. Burroughs later namechecked both Boas and Mead in anthropology-themed jokes that appear in Naked Lunch.

During the early 1930s, the rival anthropology departments at Columbia and Harvard represented a schism in the discipline about the scientific validity of biological race. Boas, a German Jew who founded the anthropology department at Columbia in 1902, had made a career of arguing that race was unscientific and that so-called “scientific” concepts of race would almost certainly be co-opted as a justification for political violence (a sentiment that was soon proven definitively by the Holocaust). For Boas and his students, supposedly fixed physical characteristics associated with race were actually malleable over even a few generations. More importantly, these characteristics had no inherent meaning. Culture was everything.

Harvard’s anthropology department during Burroughs’ undergraduate years was the antithesis of Columbia’s, with an emphasis on constructing racial typologies from craniometric data (measurements of the skull)—a practice that was to the Columbia anthropologists an outdated form of physical anthropology left over from the 19th century. In large part because of the the legacy of Harvard zoologist Louis Agassiz, a giant in the field of scientific racism, Harvard advocated for a polygenic model of human origins. Polygenists believed that distinct human races evolved in geographic isolation from one another and at separate times. This of course left the door open for fallacious ideas about the intellectual and moral superiority of certain races—a natural order of “more highly evolved” and “less highly evolved” humans that was a convenient rationale for racial hierarchies. Boas, in contrast, was a monogenist, believing that humans comprise one species with a shared evolutionary history, a belief that was confirmed in 2003 with the completion of the Human Genome Project, which proved all living humans are 99.9% identical at the level of DNA and that there is no scientific basis for race.

Unsurprisingly, polygenism was popular among American segregationists because it gave a scientific veneer to the political goals of Jim Crow. Among the scientific racists who held positions in prominent anthropology departments, few were more notable than the controversial scientist Carleton Coon, with whom Burroughs took anthropology courses at Harvard. Coon was the author of The Origin of the Races, a book declared racial pseudoscience by his peers, particularly rival Columbia anthropologist Ashely Montagu, immediately upon publication. This didn’t stop segregationists from using it to justify racial discrimination in many parts of the American South and elsewhere across the country. It’s hard to know how Coon’s ideas affected Bill. But it seems no coincidence that some of Burroughs’ most brutal and scathing satires, such as the “County Clerk” chapter from Naked Lunch, are powerful invectives against not just racial violence but the entire despicable cancer of American White Supremacy.

After graduating from Harvard in 1936, Bill began to receive a $200 monthly allowance from his parents, which he continued to collect until he was fifty years old (the true sine qua non of his literary output). This was enough for a modest Grand Tour of Europe that ended in Vienna, a city that at that time had a vibrant queer community. Bill enrolled in medical school at the University of Vienna, but by the fall of 1937 it was clear that Hitler would annex Austria, and Bill returned to the US, but not before going to the American embassy to marry a friend, a German Jew named Ilse Klapper, in order to help her escape.

Bill made several more half-hearted attempts at graduate school: a couple of semesters of uncompleted graduate courses in psychology and anthropology at Columbia and Harvard, visits to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago to learn Egyptian hieroglyphics. Nothing took root. By the early 1940s, Burroughs’ ambitions to attend graduate school were in the rearview mirror: “Life telescopes down to junk, one fix and looking forward to the next.” It would take another peripatetic decade and the threat of prison before Burroughs returned to anthropology.

IV: Van Gogh Kick

“I am going to Mexico City College on the G.I. Bill. I always say keep your snout in the public trough.”

After moving to New York City in 1944, Burroughs began living with Joan Vollmer in an apartment they shared with the writer Jack Kerouac and his wife Edie Parker, Joan’s Barnard College roommate. Joan had a young daughter, Julie, from a previous marriage and in 1947 Burroughs and Vollmer welcomed Willy, a fussy baby boy born in amphetamine withdrawal whom Bill doted on. Joan accepted Bill’s sexual preference for men, except when, like his other vices, it left them short of money at the end of the month.

In 1949, Bill was charged with drug possession in New Orleans. If convicted, the charge carried a mandatory two-to-five-year sentence at Louisiana’s notorious Angola prison. When his lawyer could no longer postpone Burroughs’ court date, the family fled to Mexico City. To complicate potential extradition to the US, Burroughs enrolled in anthropology courses at Mexico City College, which provided him with an immediate student immigration visa, and then hired a corrupt, high-octane lawyer, Bernabé Jurado, to fast track his petition for Mexican citizenship. (Thanks to his parents’ largesse, Bill was never without legal representation.)

Mexico City College was predominantly attended by former American servicemen enrolled there to qualify for the $75 monthly allowance paid by the G.I. Bill. Remarkably, William S. Burroughs, high priest of the counterculture, was also a veteran of the United States military. In 1941, he had impulsively joined the Army only to petition for an immediate discharge—arranged by his mother, of course—based on his history of mental illness. Several years prior to joining the Army, Burroughs had cut off the end of his pinky finger to impress a man he was infatuated with, a psychotic episode Bill henceforth referred to as his “Van Gogh kick.”[3] The army psychologists were more than happy to cut him loose.

In January of 1950, Burroughs was accepted to the Department of Anthropology at the Mexico City College School of Higher Studies. The department had an impressive and eclectic faculty, including Wigberto Jiménez Moreno, renowned Mexican historian and excavator of the Toltec capital of Tula, and Pedro Armillas, an influential Spanish archaeologist who had excavated at Teotihuacan. Bill registered for language courses in Spanish and Nahuatl, as well as Mayan archaeology and hieroglyphic writing. His favorite course was on the Mayan codices (bark paper hieroglyphic books detailing important astronomical, mythological, and political events in the Mayan world), taught by the polymath Robert Hayward Barlow, former collaborator and literary executor of H.P. Lovecraft. Bill was required to read Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán, a detailed account of the contact-era Maya written in 1566 by Spanish Bishop Diego de Landa, lead inquisitor of the Yucatán. De Landa is infamous for orchestrating an auto-da-fé in July of 1562 in which tens of thousands of Mayan religious idols and at least 27 codices were burned. (Today there are only four surviving pre-Columbian Mayan books, the Dresden, Madrid, Paris, and Mexico codices). Ironically, just as de Landa was working furiously to erase the Mayan calendar and religion, he was also translating their language and writing a description of the Maya in the Relación, a book that—400 years later—would become key to deciphering their written language. De Landa’s story had a profound impact on Burroughs: it was possible for a relatively small number of elites to leverage an incredible amount of power over a vast population using a combination of terrorism, language manipulation, and cultural erasure (the Catholic Church went so far as to completely outlaw the Mayan system of keeping time and forbade parents from giving children traditional Mayan names). Later, Burroughs would distill these ideas into his own theory of power which he referred to as “Control”, a recurrent theme in his work.

At first, Mexico City seemed ideal. Neighbors were paid to take care of the children, and Bill and Joan joined the party scene centered around The Bounty, a local bar frequented by American expats. Together they went on excursions led by the Mexico City College faculty to archaeological sites like the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent) at Teotihuacán. In a story from the “Personalities on Campus” section of the MCC student newspaper The Collegian from February of 1951, Bill is portrayed as a sort of jack of all trades-cum-gentleman farmer, a mix of fact and self-mythologizing that conveniently omits the Burroughs’ family fortune:

William Burroughs’ vocations have been as varied as the countries he has visited since he first left home at 18. He has been a detective, copy writer, newspaper reporter, farmer, and medical student. He has partially satisfied his wanderlust by visiting France, Austria, Greece, Yugoslavia, Italy and Albania…He graduated from Harvard in 1936 with a degree in English literature and a minor in anthropology…After the war he decided to raise cotton on a farm in the Rio Grande Valley. After he is awarded his higher degree, he is contemplating the observation of Central and South America as farming possibilities.

In reality, although Bill had been clean when they arrived, and seemed genuinely interested in his graduate courses, it didn’t last. (“As soon I hit Mexico City, I started looking for junk.”). In her letters, Joan alludes to her anger that Bills’ growing heroin habit was interfering with his motivation to visit Mayan archaeological sites, his ostensible focus. When Jack Kerouac arrived in Mexico City to party that summer, Burroughs withdrew from his anthropology courses, submitting a course withdrawal note citing acute back pain…from a pediatrician.

V: The Mayan Caper

“The Mayan codices are undoubtably books of the dead; that is to say, directions for time travel.”

Although Burroughs didn’t take graduate school seriously, he certainly got a lot of literary miles out of it over the next half century. His knowledge of the ancient Maya, particularly the Mayan calendar, is featured heavily in three of his novels, The Soft Machine (1961), The Wild Boys (1971), and Ah Pook is Here (1979), named for Ah Puch, the Mayan god of death, childbirth, and regeneration. Perhaps the most well-known—and cogent—of these stories is the “The Mayan Caper” chapter from The Soft Machine. In it, a time traveling secret agent, Joe Brundige, studies ancient Mayan culture with a team of archaeologists in Mexico City in preparation for his mission. Once he is fluent in the language, his mind is transferred via a hideous, violent process into the body of a young man from the Yucatán, whose physical appearance, unlike Joe’s, will not attract attention. Brundige travels a thousand years back in time to the height of the Mayan civilization, emerging from the future in a field filled with Mayan peasant farmers using sharp sticks and gourds to plant seed corn. Posing as one of the field workers, Joe learns that the populace is ruled with an iron fist by a tiny priestly caste that uses the hidden the symbols and secret numerology of the Mayan calendar to exert complete telepathic control over the peasantry, who plod through life in an obedient stupor. After witnessing various orgies of human sacrifice and religious violence, Joe is finally able to overpower the priests and free the enslaved workers (“Cut word lines—Cut music lines—Smash the control images—Smash the control machine—Burn the books—Kill the priests—Kill! Kill! Kill!”).

You don’t have to be a professional archaeologist to know that Mayan priests were not gods of death in possession a sacred calendar that allowed them to telepathically control the peasants like puppets—an idea Joan suggested to Bill—nor can a time machine be powered by the violent death of young man at the peak of orgasm (but, Peter Thiel, if you’re listening…). However, as Paul Wild points out in his essay “William S. Burroughs and the Maya Gods of Death”, Burroughs’ depiction of violence, spectacle, and human sacrifice among the Mayan elite as a means of social control was surprisingly prescient. Until the Mayan glyphs were deciphered in the late 1980s, archaeologists had long considered the Maya to be a civilization largely without violence. Early Mayanists like J. Eric Thompson and Sylvanus Morely had witnessed the horrors of two consecutive world wars and, lacking written records, were inclined to portray them as a peaceful theocracy led by benevolent priests who were obsessed with time and astronomy. When the Mayan glyphs were fully deciphered in the late 1980s, however, it became clear that they were lead by divine rulers who routinely waged war on one another, and frequently presided over public spectacles of violence and human sacrifice. Burroughs understood the Maya well-enough to intuitively see the arrival of the Catholic Church during the 1500s as one coordinated system of elite Control stepping into the void created by the collapse and fragmentation of the Mayan Postclassic civilization.

VI: We Must Find That Scientist

“South America does not force people to be deviants. You can be queer or a drug addict and still maintain position.”

With his interest in his graduate school waning, Burroughs found a new pursuit: Lewis Marker, a lanky twenty-one year old army veteran also attending Mexico City College on the G.I. Bill, whose agenda in Mexico was to “get rich, sleep till noon, and fuck ’em all!” At first drinking buddies at The Bounty, Burroughs grew more and more infatuated with Marker. Bill’s obsession with Lewis and their travels through Ecuador together in search of yagé form the basis of Queer, his surprisingly tender autobiographical novel, written in 1952 but not published until 1985 due to its subject matter. The comedy routines that Burroughs gave legendary dramatic performances of at his readings (e.g. “Dr. Benway Operates”) were initially developed as short skits to entertain and seduce Marker, who was not gay and who told Bill more than once that he was only interested in friendship.

Feeling rejected, Bill was a hot mess during the spring of 1951, which would prove to be the worst year of his life. In March, he managed to kick his heroin habit again—by staying as drunk as a skunk for a month, drinking from morning until night with Joan, who was coping with her own withdrawal from amphetamines. As he details in his first novel, Junky, the bender had him coming apart at the seams: “My emotions spilled out everywhere. I was uncontrollably social and would talk to anybody I could pin down. Several times I made the crudest sexual propositions to people who had given no hint of reciprocity.” After a few botched, drunken sexual encounters with Marker, Burroughs forced himself to the look at the facts. Lewis had a visceral reaction to his touch and in Bill’s estimation “not queer enough to make reciprocal relation possible.” He was so heartbroken that his entire body ached, and for weeks he was given to crying jags. Waiting for Marker to come around was like waiting for Godot. The public perception of Burroughs as cold and incapable of love really couldn’t be further from the truth.

At The Bounty, Burroughs had regaled Marker with tales of a mysterious drug named yagé found at the headwaters of the Amazon, a drug that purportedly gave users telepathic abilities.[4] Though the preparation of the drug was a secret closely guarded by shamans, scientists had recently isolated the active ingredient, “telepathine.” Burroughs proposed they travel to Ecuador together, and use their combined skills to find a source of the plant and to identify it. But Marker, a level-headed former counterintelligence officer with no time for telepathy or shamans, had zero interest.

Marker’s attitude did a quick 180 when Bill received a sizable chunk of cash from the sale of the Burroughs’ farm in Texas a few weeks later. At the tail end of a night of drinking at The Bounty, when the newly flush Burroughs asked Marker one last time about that trip to South America, just the two of them, Lewis replied, “Well, it’s always nice to see places you haven’t seen before.”

They made an agreement: for the duration of the trip, Bill would pay for all of Marker’s travel expenses in exchange for sex twice a week. When Lewis asked how, without any training, they would even know where to begin, Bill replied, “A Colombian scientist isolated Telepathine from Yage. We must find that scientist.” Marker was capable and good with logistics, and the arrangement seemed to work. For a while.

Bill and Lewis set out on what would ultimately be a three month journey, first traveling by bus to Panama, and then by boat and plane to Quito, Ecuador, where Burroughs hoped to make contacts who would point them in the right direction. After several dead ends, Burroughs learned that yagé grows high in the Andes and could mostly easily be found in the Putumayo region of northern Ecuador. Feeling that they were finally on the right track, a reenergized Burroughs treated Marker to dinner and brothel before setting out the next day.

The comically underprepared pair found themselves on a riverboat up the Guayas River in southwestern Ecuador, “Swinging in hammocks, sipping brandy, and watching the jungle slide by.” Although the conditions along the way grew increasingly difficult, in the novel Queer, Burroughs characterizes their journey somewhat romantically. On a fourteen-hour bus ride across the Andes, they passed the snow-covered peak of Chimborazo, the tallest mountain in Ecuador, “huddled together under a blanket, drinking brandy, the smell of wood smoke in our nostrils.” The route took them along the edge of a thousand-foot gorge, and the bus had to stop several times to remove rocks from the road in order to pass.

When they finally arrived at their destination, the town of Puyo in central Ecuador, the exhausted pair met a Dutch farmer who gave them directions to the home of an American scientist living in the jungle, a botanist who was rumored to be isolating a rainforest drug that would make him a fortune. If anyone in the area knew where to find yagé, the scientist would know.

The following day, Bill and Lewis set out again, bringing bottles of tequila with them to grease the wheels if necessary. It began to rain incessantly, and the corduroy road through the jungle became slippery and filled with mud. They ventured further and further into their own particular heart of darkness, eventually reaching the home of the mysterious Dr. Cotter, who was instantly suspicious that the pair was there to steal his research. Bill attempted to ply the scientist with tequila, but succeeded only in getting himself drunk. He sloppily attempted to explain their search, and although Dr. Cotter had heard of yagé, he equivocated as to its whereabouts. The botanist let them stay for a few days, but it was clear he had no desire to help them. Mostly he just wanted to be rid of the odd pair of drug tourists.

Following this dead end, the money ran out, and with it Lewis’ patience. Empty handed, they flew back to Mexico City and parted ways. Though Burroughs had known the affair was doomed from the start, he was crushed all over again.

VII: Annus Horribilis

“I hope Bill Burroughs goes to hell and stays there.” — Dorothy Vollmer

A few days after Bill returned from Ecuador, the lives of the Burroughs family changed irrevocably. The story is worn thin from repetition: at an alcohol-soaked gathering above their favorite bar, Joan challenged Bill, who prided himself on his excellent marksmanship, to shoot a drinking glass off her head, a party trick they had most likely had performed before. Bill aimed and pulled the trigger and the shot rang out. The glass fell and rolled on the floor, and Joan’s head slumped to the side. For a split second it seemed as if she was playing a practical joke. Lewis Marker, who along with friend Eddie Woods was the only other person in the room, said Bill, I think you hit her.

Bill yelled “No!” and ran to Joan’s crumpled body. Seeing a small hole in her temple, he realized in horror that he had missed the glass and shot Joan instead. As he sat in shock, she was rushed to a nearby Red Cross hospital where she died shortly after arrival on September 6th, 1951. Vollmer was just twenty-seven years old.

In a single moment of drunken recklessness, Bill had destroyed his entire family. Joan was gone forever. Mort, Bill’s brother, flew to Mexico City and made funeral arrangements, and brought Willy and Julie back the family home in St. Louis. When the Vollmers decided to raise Julie on their own, the children were subsequently split up; Bill never saw Julie again. Joan’s mother Dorothy stated simply, “I hope Bill Burroughs goes to hell and stays there.”

So much has been written about the nature of Joan Vollmer’s death—entire graduate school careers constructed around it—and so much time has passed that it is hard discern myth from reality. Burroughs’ amanuensis and literary executor James Grauerholz has written an in-depth analysis corroborating details from the eye-witnesses, press coverage, police reports, and family friends that is likely the closest anyone will ever to come to the truth. One thing that everyone—the witnesses, the police, the lawyers, the judge, family friends—agrees on is that although Bill was responsible, he had no intention of killing Joan that night. Which meant nothing to her family or the children, of course.

Until the end of his life, Bill wrestled with accepting full responsibility for Joan’s death. In the 1960s, he began to speculate that an evil entity, dubbed the Ugly Spirit ("the worst part of everyone’s character”), caused him to shift his aim at the last second and shoot Joan rather than the glass. In the introduction to Queer, Burroughs mythologizes the tragedy as the moment he was born as an author: “So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.”[5] On one hand, Burroughs believed in the influence of supernatural forces. On the other, it’s pretty clearly a self-serving mea culpa.

VIII: The Algebra of Need

“Desperation is the raw material of drastic change.”

Burroughs was arrested for homicide and released on bail after two weeks in jail. Despite the Ecuador debacle, Lewis Marker proved to be a loyal friend in the aftermath of Joan’s death. He testified to the accidental nature of the shooting to the police, managed Bill’s affairs while he was in jail, and moved into his flat for a few months to help get Burroughs back on his feet. Soon enough, however, Bill began to talk romantically about plans to get little Willy back and travel across South America with “both of his boys”, the three of them perhaps settling down on farm in Panama. After all he had done for Bill, Lewis had had it with him. Why couldn’t they just be friends with no sex?

After Lewis returned to his parents in house Florida that Christmas, he effectively stopped communicating with Burroughs. Back in Mexico City, Bill held out hope, pined for letters from Lewis that never came, and composed unrequited love poetry. In burst of productivity during the spring and summer of 1952, he wrote his second novel, Queer, which Burroughs dedicated to Marker, a feat Bill rather absurdly thought would win him over (but a definite improvement over cutting off his own finger). Burroughs was plagued by dreams about Willy and Joan, and drifted in and out of heroin addiction and alcoholism. When Jack Kerouac arrived in Mexico City to lift his spirts while Bill was awaiting trial, he found a broken man: “[Bill] misses Joan terribly. Joan made him great, lives on in him like mad, vibrating.” But Jack Kerouac was always saying shit like that.

In a letter to Alan Ginsberg that summer, Burroughs wrote, “I want to get out of Mexico. There is nothing more left for me to do here. Jack returns to US July 1st. I am going to S.A. alone. I offered to pay Marker’s expenses if he would come with me. No answer. I guess he means no.”

Waiting for his trial that never seemed to arrive[6], in November of 1952 another episode of violence turned Burroughs’ world upside down: Bernabé Jurado, his cocaine-fueled lawyer, shot and killed a teenager in a road rage incident and fled to Brazil. When Jurado’s law partners shook Burroughs down for more money, he lost confidence in his case and did what he always did in a crisis—fled into the arms of his parents, who were now living in Palm Beach, raising Willy in their golden years.

Out of desperation, Burroughs became more determined than ever to find yagé. Going on little more than a hunch, he pinned all of his hopes on the idea that this drug alone had the power to free him of his addiction, to cut through his depression, and to help him come to terms with the trauma of killing his wife and losing everyone he loved. He wrote to Ginsberg, “I may lose my bond money, but I must go. I must find the Yage.”

IX: Vine of the Soul

“I must give up the attempt to explain, to seek any answer in terms of cause and effect and prediction, leave behind the entire structure of pragmatic, result seeking, use seeking, question asking Western thought. I must change my whole method of conceiving fact.”

Yagé is an entheogen (“becoming divine within” in Greek), a class of mind-altering drugs that includes peyote, San Pedro cactus, psilocybin mushrooms, and many other plants used by indigenous groups for divination and healing. The drug is a decoction of two plants: the chacruna shrub, which contains the powerful psychedelic DMT, and the caapi vine, which contains an MAO inhibitor that prevents the DMT from being degraded in the liver. In 2019, archaeologists conducting a chemical analysis of 1,000-year-old ritual bundle from a rock shelter in highland Bolivia found both ingredients of the yagé mixture (chacruna and caapi) and a kit with tools for storing and taking the drug, illustrating the deep antiquity of this knowledge. The ritual use of yagé no doubt predates this single archaeological site, likely stretching back thousands of years.

As an undergraduate, Burroughs had read the first English account of yagé, Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes, a travelogue published by Victorian explorer Richard Spruce in 1853. Spruce was the first to draw the caapi plant, known locally as the “vine of the soul”, give it a preliminary classification (Banisteria caapi), and make note of his experience drinking, as he put it, a “cup of the nauseous beverage” at a Takano caapi festival in northwestern Brazil. Although many anthropologists, botanists, and missionaries encountered the caapi vine over next seventy years, little progress was made in identifying the chemical components of the drug until 1923 when Colombian chemist Guillermo Fischer-Cárdenas isolated an alkaloid from Banisteriopsis caapi and named it “telepathine” (later renamed the more prosaic “harmine”).

In the 1920s, pharmaceutical companies like Merck, which had created MDMA in the lab in 1912, started to become interested in the substances used in non-Western traditional medicines, referred to as “phantasticants.” The company scoured South America for new drugs to develop, working with scientists to identify medicinal plants and psychoactive substances. In particular, Merck spent over a decade trying to develop a drug from the harmine alkaloid, importing tons of caapi vine from the Amazon to Berlin, not to create a mind-altering substance but to develop a drug to cure Parkinson’s disease.[7]

Burroughs refers to research and correspondence regarding both the caapi vine and “telepathine” that he had conducted before leaving for South America, but stated that in general:

References to yagé were vague and contradictory. I gathered that the informants had not taken yagé themselves, but were merely repeating unconfirmed statements they had heard from someone else. I did learn that the scientific name for yagé is Banisteria Caapi. Since it is used throughout the Amazon Basin by various Indian tribes speaking perhaps a hundred different languages, there are many Indian names: yagé, ayahuasca, nepi, nateema, this last used by the Jívaro head hunters of Peru and Ecuador.

At the same time Bill was researching yagé, other literary figures were beginning to publicize their own psychedelic trips. Burroughs was first inspired to turn his yagé experiences into a book after reading Aldous Huxley’s popular The Doors of Perception (1954), which details Huxley’s earthshattering experiences with mescaline. In 1957, LIFE, the most widely circulated magazine in America at that time, published “Seeking the Magic Mushroom” by Gordon Wasson, Vice President of PR at JP Morgan and psilocybin enthusiast. Thus, while his expedition might appear to some as pseudo-scientific drug tourism by a trust fund kid (which it certainly was in some respects), at the time, and given his pedigree, Burroughs’ yagé quest had an air of legitimacy it would not today.

X: My Past Was an Evil River

“Sure you think it’s romantic at first but wait until you sit onna sore ass sleeping in Indian shacks and eating Yoka and some hunk of nameless meat like the smoked pancreas of a two toed sloth.”

Burroughs spent the next eight months travelling through Columbia, Ecuador, and Peru looking for yagé. The journey is described in his novel The Yage Letters, a book of fictional letters between Burroughs and Ginsberg based on their actual South American travel correspondence, described by writer Alan Ansen as a “anthropo-sociological travelogue.” It was the first modern account of an ayahuasca trip, and for decades the only book on the subject in America. From its cover, a photo of a tripping Makuna shaman that Burroughs personally selected from the Harvard Botanical Museum, you could easily mistake The Yage Letters for a mid-20th century ethnography—a work of science. (Similarly, an obscure YouTube clip from a documentary about ayahuasca with narration by him could easily pass for an ethnographic film, if not for Burroughs’ unmistakable staccato voice.) But the opening lines of the book about Bill’s hemorrhoid surgery in a Panamanian hospital (“I stopped off here to have my piles out. Wouldn’t do to go back among the Indians with piles I figured.”) immediately undercut any expectation of scientific objectivity, disarming the reader in the same way as the first line of Claude Lévi-Strauss’ memoir of the Amazon, Tristes Tropiques: “I hate traveling and explorers.”

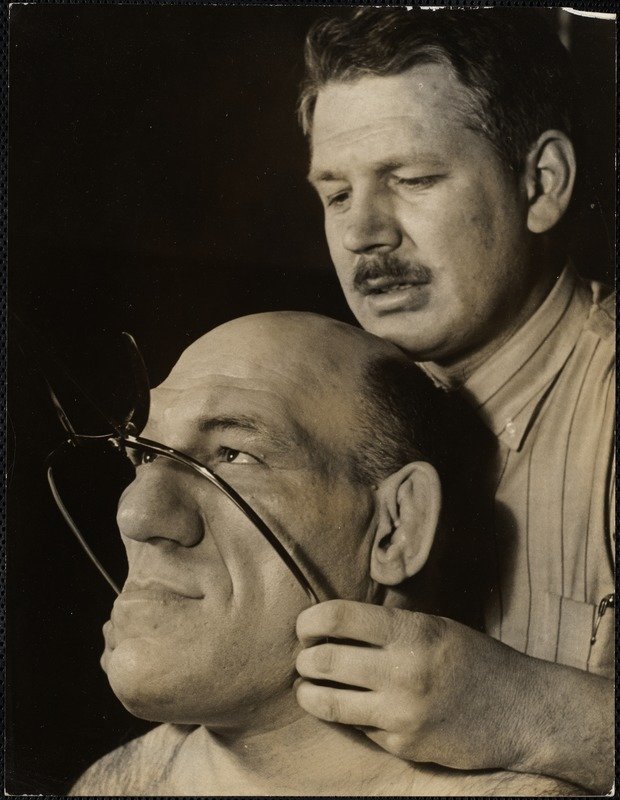

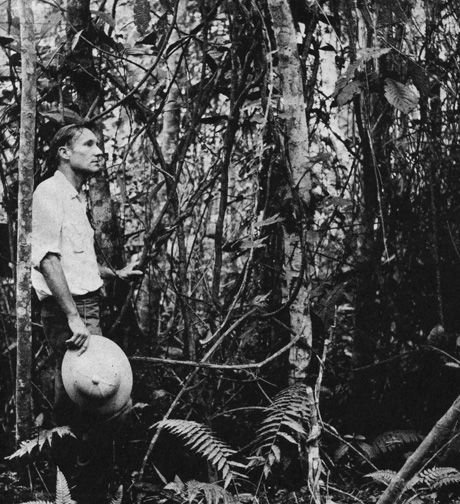

From Panama, Burroughs finally made it to Bogotá, where he hoped to find a botanist who could provide him with more detailed scientific information. Bill’s first stop was the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia where he had an incredible stroke of luck. After wandering through the dank, dusty hallways, he came to a large room filled with plant and animal specimens, smelling of formaldehyde. At the back of the room, Bill spotted someone searching the shelves with great irritation. “The man had a thin refined face, steel rimmed glasses, tweed coat and dark flannel trousers. Boston and Harvard unmistakably.” Burroughs hadn’t just found any plant specialist, he had found the plant specialist: legendary Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Schultes, an authority on South American hallucinogens, who in 1953 happened[8] to be working for in Bogotá the US Agricultural Commission.

Although both had been undergraduates at Harvard in the early 1930s, Schultes and Burroughs hadn’t known one another. Schultes had taken his coursework seriously, writing his senior thesis on the medicinal properties of the hallucinogenic peyote cactus used by Native Americans in Oklahoma. He went on to receive his PhD from Harvard in 1941, and won a fellowship to conduct field research on curare (the poison used in poison darts, eventually developed as a paralytic drug for surgery) in the Amazon jungle, where he somewhat mythically disappeared for the next twelve years. Schultes went on to teach ethnobotany at Harvard for decades, collecting over 25,000 plants and authoring hundreds of books and articles about rubber, hallucinogens, orchids, you name it. His most famous book, Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers, co-authored with Albert Hoffman, the inventor of LSD, has never been out of print. On top of that, Schultes was a pioneer of rainforest conservation. He was everything that Burroughs was not, and the type of Harvard man Burroughs romantically aspired to be, albeit in a fantasy world where that sort of thing didn’t take decades of hard work and dedication.

Schultes laughed at the idea that yagé could make users telepathic, but was willing to show Burroughs a few dried specimens of caapi vine. Surprisingly, although he had experimented with most of the South American drugs he encountered, Schultes had yet to experience yage’s full effect.[9] He conjectured that the active ingredient was in the inner bark of the caapi vine, but was unsure about the nature of the other plants the curanderos added to the boiling brew, and if these ingredients were inert or essential. He handed Bill a map of the Putumayo and told him the pharmacopeia he would need to assemble for his expedition: anti-venom serum, anticonvulsants, antibiotics, anti-diarrheal drugs, anti-malaria drugs, among others. Clearly the jungle wanted you dead.

XI: All I Want Is Out of Here

“I’ve seen villages in South America with no police whatever. Then the cops would arrive, then the sanitary inspectors, and before you know it they’ve got all the problems—crime, juvenile delinquency,

In the early 1950s, the Amazon was crawling with anthropologists, most notably Swiss humanitarian Alfred Métraux, pioneer of Structuralism Claude Lévi-Strauss, activist Audrey Butt Colson, and radical Pierre Clastres. Each had gone to the Amazon hoping to make contact with near “pristine” cultures untouched by the State, and returned to report that isolated tribes were not all that isolated, and that, in fact, for hundreds of years had been moving away from the dangers posed to them by encroaching Colonialism. In particular, after witnessing the horrors of “Civilization” that accompanied the Amazon Rubber Boom of 1870-1911—a genocide accompanied by slavery, forced labor, and epidemics of measles and influenza—many indigenous groups in the Putumayo decided they wanted no part of civilization and made themselves scarce.[10] Everywhere he went, Burroughs saw evidence of “Dutch Disease”[11], an economics term for when the discovery of an abundant natural resource is disastrous for local communities long-term. Bill realized that the “economic development” he had heard about in the Putumayo was simply a euphemism for the extraction of oil, which had gone from creating prosperity for local communities to creating dependence. “Everyone in the Putumayo believes the Texas Company [Texaco] will return. Like the second coming of Christ.”

While traveling through the Putumayo, Burroughs had no problem obtaining samples of caapi vine, which gave him a small, almost imperceptible buzz, but not the full effect. Unable to find a knowledgeable yagéro to correctly prepare it for him, Bill returned to Bogotá, stymied.

In a second extraordinary stroke of luck, Schultes was able to get Burroughs official papers from the Colombian Foreign Office to allow Bill to join the next Anglo-Columbian Cacao Expedition to the Amazon, a thousand mile round trip. Burroughs’ letter to Ginsberg about returning to the Putumayo reads like a passage from Heart of Darkness:

I have attached myself to an expedition—in rather a vague capacity, to be sure—an expedition of varied purposes and personnel: Dr. Schultes; three Swedish photographers who intend to capture a live anaconda; two Englishmen from the Cocoa Commission (whatever that is), and 5 Colombian ‘assistants.’ A whole truck-load of gear is on the way down, boats and tents and movie cameras and guns and rations.

Columbian officials were mistakenly under the impression that Burroughs was a Texaco oil executive, and he was given first-class transportation and accommodations in the governor’s house. When the expedition arrived at the capital of the Putumayo, Mocoa, Bill made an appointment with an Ingano medicine man. The following day, Burroughs, accompanied by Schultes and Paul Holiday, another member of the Cocoa Commission, walked ten minutes outside of town to the home of the local curandero.

“You’ve come to the right place,” the Ingano man said. Next to him was a small shrine containing the Virgin Mary, a crucifix, a wooden idol, and some feathers and little packages tied with ribbons—his own syncretic offering. The old man poured a viscous black liquid, phosphorescent like an oil slick, into a dirty red cup and said, “Just drink this straight down.” Burroughs tossed it back and immediately felt nauseous.

The effect was overwhelming. In a diary entry by Paul Holiday written the following day, he wrote, “The old Ingano Indian gave him a wineglass full of the stuff, and within 15 min. it sent him off his rocker: violent vomiting every few minutes, feet almost numb & hands almost useless, unable to walk straight, liable to do anything one would not dream of doing in a normal state.”

Disoriented, Burroughs lunged outside to vomit, but his feet felt like bricks, causing him to run into the door frame. Vomiting probably saved his life: a man whom the curandero had given a similar dose to few weeks earlier had allegedly run into the jungle and died in convulsions. Bill spent the rest of the ceremony sick and gasping for air, crouched behind a rock, completely deranged, repeating All I want is out of here, all I want is out of here over and over again.

He eventually remembered the Nembutal tablets (a powerful sedative) he had in his pocket, and with trembling arms and legs managed to crawl to a stream to get a mouthful of water through his clamped jaws to swallow them. The Nembutal neutralized the worst of the effects of the yagé, and Burroughs collapsed under a blanket on the dirt floor of the hut to sleep it off.

Aren’t drugs fun?

A few days later, a fully-recovered Bill Burroughs, still a Texaco Oil executive as far as Columbian officials were concerned, was on his way back to Bogotá in a chauffeured car courtesy of the Agricultural Commission. When he arrived, he wrote to Ginsberg: Mission accomplished. I have a crate of Yage with me. I know how the witch doctors prepare it. I have taken it three times. (1st time came near dying.) I am not going to take any more until I extract the pure substance free of nauseating oils and resins. A large dose of Yage is sheer horror. I was completely delirious for four hours and vomiting at 10 minute intervals. As to telepathy, I don’t know. All I received were waves of nausea.

But after returning to the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Burroughs and Schultes were unable to extract the alkaloid that precipitated the desired effect. (In reality, they lacked the key ingredient, the DMT-containing chacruna leaves). Realizing that he was still missing a key element, Burroughs consoled himself with a cocktail of laboratory alcohol and Pepsi, and made plans to travel next to the Ucayali River valley in Peru, homeland of the Shipibo people, known for their own ayahuasca ritual.

XII: Hold the Presses!

“I was traveling because I was a man trying to escape from himself.”

When he arrived in Lima in May of 1953, Bill learned he had been convicted of homicide in Mexico and given a two year sentence in absentia. Judge Eduardo Urzaiz had actually handed down a suspended sentence, but due to some misunderstanding Bill didn’t realize this for some time. Feeling he truly was in exile now, he spent the next two months traveling alone through Peru, eventually arriving in Pucallpa, a river town located on the banks of the Rio Ucayali. Bill’s letters make it clear he had finally found what he had been searching for:

Hold the presses! Everything I wrote about Yage subject to revision in the light of subsequent experience. It is not like weed, nor anything else I have ever experienced. I am now prepared to believe the Brujos do have secrets, and that Yage alone is quite different from Yage prepared with the leaves and plants the Brujos add to it…I took it again last night with the local Brujo. The effect can not be put into words…I experience first a feeling of serene wisdom so that I was quite content to sit there indefinitely. What followed was indescribable. It was like possession by a blue spirit.

Engaging in what anthropologists refer to as “deep hanging out”[12], Burroughs was able to get samples of the “secret” ingredient from a friendly yagéro, writing in his notes that, “Addition of other leaves which I have identified as Palicourea Sp. Rubiaceae[13] is essential for full hallucinating effect.” For decades, the research had focused on what seemed like the obvious active ingredient—pounds and pounds of freshly shaved and chopped caapi vine. As Oliver Harris writes in his introduction to the revised version of The Yage Letter Redux, in realizing that the chacruna leaves were the missing ingredient, Burroughs had made perhaps most significant botanical discovery regarding the use of yagé since Richard Spruce a century earlier.

By July of 1953, Bill had developed a tolerance and could ingest yagé without getting sick: “This was the first time I dug the kick.…it is like nothing else. This is not the chemical lift of C, the sexless, horribly sane stasis of junk, the vegetable nightmare of peyote, or the humorous silliness of weed. This is insane overwhelming rape of the senses.” Burroughs, who had identified as queer since adolescence, noted after one of these trips, “Complete bisexuality is attained. You are man or woman alternately or at will…The only contact you want is sexual contact. I never experienced such sex kicks.” The effect seems to have been short lived, however.

From his hotel room in Lima that summer, Bill wrote to Ginsberg, “Yes Yage is the final kick and you are not the same after you have taken it, I mean literally.”

But yagé was not the final kick for Burroughs. Not even close.

The most notorious part of his life had just started. In the fall of 1953, pulp fiction giant ACE books published Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict (later retitled Junky) which introduced a thinly veiled William Burroughs to America as William Lee, an emotionless criminal driven to petty theft to feed his heroin addiction. Around the same time that Schultes returned to Harvard to build his illustrious scientific career, Burroughs moved to Tangier, where he started to write Naked Lunch, a psychic distillation of all of the anxieties of post-war America, a horrorshow of everything Americans were afraid of, everything verboten—an anti-Capitalist, anti-White Supremacist, anti-death penalty tract depicting addiction, homosexuality, racism and sadistic sexual violence in purposefully explicit terms, a dark satire in the manner of Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal.[14] And the trauma, addictions, and atrocious behavior that plagued him in Mexico City went right along with him, unresolved, from New York to Europe and on to Tangier, where there would be even fewer rules, fewer limits.

In his preparatory notes for the The Yage Letters, Burroughs comes to the conclusion that perhaps you don’t need the shaman at all: “The Brujos say they are the only ones competent to prepare it…the fact is Yage is Yage and anyone can prepare it in an hour or so if he has enough of the Yage vine.” Bill was blind to the fact that for most people, the inclusion of a shaman is not a bug, it’s a feature. His ethnocentric disregard for an important tradition that had successfully persisted for over a thousand years in the Amazon, is another example of how, as Oliver Harris notes, Bill played the Ugly American rather ambiguously.

Of course, Burroughs was wrong. For any lasting healing, or even a simple, clear-eyed assessment, you need the shaman, the curandero, the therapist. The drug is not a magic bullet, as it has often been touted. For me, Burroughs’ yagé quest is a microcosm of the failure of the “Psychedelic Revolution” to translate individual transformative experiences into lasting social change—what have all of those enlightening trips added up to, collectively speaking? There has been no lasting spiritual or humanist transformation among the generations of Americans who have broadly experimented with psychedelics—if anything, it almost seems like we are collectively worse off in terms of our mental health and stewardship of the planet.

XIII: Naming the Ugly Spirit

Towards the end of his life, Joan’s death weighed more heavily on Bill. In The Place of Dead Roads he wrote:

My accidental shooting of my wife in 1951 has been a heavy, painful burden for me for 41 years. It was a horrible thing, and it still hurts to realize that some people think it was somehow deliberate. I’ve been honest about the circumstances—we were both very drunk and reckless, she dared me to shoot a glass off her head, and for God knows what reason, I took the dare. All my life, I have regretted that day.

To help him carry this “burden”, he once again turned to his knowledge of anthropology. In his seventies, Bill was finally able to accept a difficult fact that I think most people know on an intuitive level:

You can’t be your own shaman.

Which is how on a March night in 1992, Bill Burroughs found himself sitting in his underwear in the dark in a sweat lodge purification ceremony led by a shaman named Melvin Betsellie, a Diné elder from the Four Corners area of the Navajo Nation. Betsellie had been invited to Burroughs’ house in Lawrence by William Lyon, a mutual friend and professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas. The shaman passed around a long tobacco pipe and used a feather to waft smoke over the participants. Water and cedar chips were thrown on the stones in the firepit, and exploded in clouds of steam that Burroughs found unbearably hot. Bill realized not only might the ceremony fail, but that Betsellie was actually in pain from the strength and intensity of whatever he was grappling with. Bill was desperate for air, begging to get out, but was encouraged to stay until Betsellie caught the “the entity” in a flute and blew it into the fire. The ceremony continued on inside of the house for hours as Betsellie chanted prayers in Navajo, imploring his ancestors and the spirits to give Bill a peaceful life free from the entity, which he described as a white skull with no eyes and wings. William Lyon later said of the encounter, “It scared Betsellie on a deep shamanic level…it hit him harder than he anticipated.”

Burroughs seemed to get some closure from the ceremony, telling friends, “This is the same notion, Catholic exorcism, psychotherapy, shamanistic practices—getting to the moment when whatever it was gained access. And also to know the name of the spirit. Just to know that it’s the Ugly Spirit. That’s a great step. Because the spirit doesn’t want its name to be known.”

Postscript: Liberation in the Imaginary

“In my writing I’m creating an imaginary world in which I would like to live.”

Part of Burroughs’ 1981 novel Cities of the Red Night revolves around a colony of queer abolitionist pirates and former slaves, a sort of revisionist history of the 18th century in which their military campaign to defeat the European powers’ transatlantic slave trade catches fire around the world (“our most powerful weapon is the freedom hopes of captive peoples enslaved and peonized”). Given historical estimates that something close to three-quarters of the world’s population was in some form of bondage at this time, there is a certain logic to the idea. The colony in the novel is loosely based on Libertalia, an apocryphal pirate republic settled on the coast of Madagascar by abolitionist Captain James Misson in the late 1600s. Due to the exigencies of mutiny, pirate ships were ethnically and culturally diverse experiments in egalitarianism: public school-educated Englishmen might find themselves working alongside not only Swedes, Italians, and other Europeans, but Arabs, Caribbean creoles, Native Americans, Africans, Malaysians, and other escaped slaves. Pirates typically freed the slaves on ships that they captured (who, understandably, often joined the pirates), and pirate crews elected and removed captains democratically. Libertalia was simply a logical extension of these principles on dry land. It became the most famous “pirate utopia” in Europe and its colonies during the Enlightenment, in particular for its “Articles”, a legal document that purportedly abolished slavery, racial and religious castes, and outlined individual rights and the equal division of property. In his introduction to Cities of the Red Night, Burroughs paints Libertalia as a sort of Eden for non-conformists, one we have been permanently cast out of: “Your right to live where you want, with companions of your choosing, under laws to which you agree, died in the eighteenth century with Captain Mission [sic].”

The late David Graeber, perhaps the most important anthropologist of the early 21st century, points out that there is no historical or archaeological evidence that Libertalia, or Misson, ever existed. For Graeber, however, Libertalia’s existence is trivial[15]: its actual importance was its immensely popular reception as a vision of human rights and human potential, an alternative to the absolute nightmare of European Colonialism. Graeber, one of the most influential theorists of what borderless, post-Capitalist societies might actually look like, reminds us that our present moment of unfettered Capitalism and militarism is in no way inevitable or even representative—anthropologists provide us with a great deal of evidence that humans have always found and continue to find radically new ways to organize themselves.[16] Graeber suggests we should give ourselves permission to imagine scenarios outside of what we think is possible in the present:

This is what I mean by “liberation in the imaginary.” To think about what it would take to live in a world in which everyone really did have the power to decide for themselves, individually and collectively, what sort of communities they wished to belong to and what sort of identities they wanted to take on—that’s really difficult.

In the end, Burroughs’ importance isn’t his books or his life, it’s a reminder, a buoy, that radical acts of imagination—not unlike the experience of other cultures—allow us not only to see our own society more clearly, but to create spaces in which people can begin to poke and prod at the thin skin of illegitimate power and authority. To remind us that when you cut into the present, the future leaks out.

Footnotes:

[1] The Haitian Revolution of 1791, the most spectacular and successful slave revolt in world history, was orchestrated by Vodou “sorcerers.”

[2] In 1888, Bill’s grandfather, William Seward Burroughs I, patented a part which greatly improved the functionality of the adding machine. Burroughs Adding Machines were quickly adopted by the banking industry, resulting in a small family fortune.

[3] Burroughs’ “Van Gogh kick” is described in surgical detail in his short story The Finger.

[4] Bill and Joan claimed to be able to communicate with each other telepathically, and were true believers.

[5] This isn’t strictly true, as Burroughs had completed portions of Junky before Joan’s death.

[6] In a letter to Ginsberg from this period, Burroughs asks him to send a copy of Franz Kafka’s In the Penal Colony, which tracks.

[7] In an odd connection, Burroughs may have inadvertently helped to find a treatment for Parkinson’s disease. In his 2016 book Mentored by a Madman: The William Burroughs Experiment, neurologist Andrew Lees, the world’s most influential Parkinson’s researcher, credits Burroughs with inspiring him to travel to the Putumayo region, where Lees discovered groundbreaking therapies to halt a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s.

[8] Burroughs would not have seen this as simply a stroke of luck. “In the magical universe, there are no coincidences and there are no accidents. Nothing happens unless somebody or some being wills it to happen.”

[9] Schultes had tried yagé, but I’m convinced by one of his remarks to Burroughs that he hadn’t experienced a true four to six hour trip, and likely ingested only the caapi vine (without the chacruna leaves), which has a mild hallucinogenic effect similar to cannabis. After witnessing Burroughs’ horrific first yagé trip, Schultes chided him, “That's funny, Bill, all I saw was colors.” Had Schultes taken a correctly prepared dose of yagé, I have no doubt that he would not have been so flippant. Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that Schultes would have been able to ingest yagé without nausea or several hours of incapacitation, another clue that he not really experienced it at that point.

[10] Studies of small, isolated groups, such as Pierre Clastres’ Society Against the State, Michal Harner’s The Jívaro, and James C. Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed, and many, many others provide a wealth of examples of indigenous groups who disappeared in the face of encroaching states and industrial Capitalism—people that have in common the notion that abnegating your personal autonomy to some distant, abstract authority is the most patently ridiculous and self-nullifying thing you could do.

[11] The recent extraction of cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo and oil in Equatorial Guinea and Angola are but a few examples of how the boon of capital created by rapid resource extraction leads to environmental collapse, violence, and social upheaval.

[12] “Deep hanging out” is an open-ended, immersive observation period in which the anthropologist is present and participatory in long informal sessions over extended periods of time—a pejorative for anthropologists like James Clifford but high praise from the likes of Clifford Geertz.

[13] Palicourea and Psychotria are chemically and taxonomically similar genera of flowering plants in the Rubiaceae family.

[14] After the ban on Naked Lunch was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1966, Burroughs noted, “It’s a tract against capital punishment in the genre of Swift’s Modest Proposal. I was simply following a formula to its logical conclusion” and “A doctor is not criticized for describing the manifestations and symptoms of an illness, even though the symptoms may be disgusting. I feel that a writer has the right to the same freedom.”

[15] As Graeber notes in Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia, there is ample evidence of hundreds of pirate settlements along the northeast coast of Madagascar, pirates who intermarried with the Malagasy in the 18th century and created many new social experiments in governance and property rights on the northeast coast of Madagascar. Their descendants, the Zana-Malata, remain a self-identified cultural group to this day.

[16] Contrary to Neoliberalism, which would have you believe that we have reached the “end of history” in terms of our political and economic evolution, a sort of World Historical game of fuck, marry, kill, in which the United States fucks liberal democracy, marries Late-stage Capitalism, and kills Communism.