The Cousins of Sarah Baartman: Anthropology, Race, and the ‘Curvaceous’ Venuses of the Ice Age

La Dame à la Capuche, one of the Venuses of Brassempouy. Ivory, 25,000 years old.

I. Beware the Ides of March

In mid-March 1892, Dr. Emile Magitot, head of the French association for the advancement of science, wrote to Édouard Piette, one of the best known archaeologists in France at the turn of the century, to inquire if he knew of an archaeological site that might serve as an excursion for the members of the association. Piette responded — foolishly, he felt, in retrospect — that he knew of a site outside of a small village in southwestern France, Brassempouy, where excavations in prehistoric deposits were already underway. The following September, forty members of the association, largely untrained and unsupervised, arrived at the site, chose a sector for themselves, and with shovels and picks and implements of destruction proceeded to zealously demolish one of the most important archaeological sites in Europe.

Rather than carefully excavate and record the location of the fragile twenty or thirty thousand-year-old figurines carved from extinct Ice Age mammoth ivory they found (as would a trained archaeologist), finders keepers ruled the day: with the exception of a few objects, an anarchic free-for-all ensued in which the day trippers simply pocketed what were likely some of the most unique treasures of Paleolithic art ever found.

Piette wanted them arrested.

None of the excursionists were, but a handful of these artifacts did trickle back to Piette over the course of the next few years. The biggest crime of all was that no one really knew exactly what went missing from Brassempouy. However, in one of those ironic twists of fate that the universe seems particularly enamored of, out of what archaeologist Henri Delporte described as the “greatest looting episode in the history of Prehistory,” came a dogged effort to find what was left at Brassempouy. This effort not only led to Piette discovering a small, 25,000 year fragment of a sculpture of a serenely faced woman wearing a hood or braided hair, but to popularize the archaeological term for the world’s oldest female statuettes: the Venus figurines.

Not to be confused with the classical Greek statues of Aphrodite, “Venus figurine” is the blanket term for a few hundred Upper Paleolithic female figurines, roughly the size of your hand, found scattered from France to Siberia. What do we know about them?

Left to right: Venus of Hohle Fels (Germany). Ivory, 35–40,000 years old .Venus of Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic). Ceramic, 25–29,000 years old. Venus of Willendorf (Germany). Limestone, red ochre, 25–28,000 years old.

〰️

Left to right: Venus of Hohle Fels (Germany). Ivory, 35–40,000 years old .Venus of Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic). Ceramic, 25–29,000 years old. Venus of Willendorf (Germany). Limestone, red ochre, 25–28,000 years old. 〰️

After over a century of scientific research, surprisingly little. We know that the first was found in France in about 1864 (la Vénus impudique, the immodest venus), and the most recent in Germany in 2008 . We know that the majority of them are Gravettian-era, that is to say 27,000 to 22,000 years old, although the earliest known example — the Venus of Hohle Fels — is 35,000 to 40,000 years old, making it the oldest undisputed example of human figurative prehistoric art in the world. Some wear woven clothing; many are pregnant or appear to have had children. Although the most well-known, iconic Venus figurine, the Venus of Willendorf, is made from stone, we know they were also made from mammoth tusk ivory, fired clay, and jet. We know that some are highly realistic, anatomically accurate depictions of women, while others are so abstract as to be hardly recognizable as female: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon of their time. And not to be overly glib, but coming from the perspective of an archaeologist, that’s about all, folks.

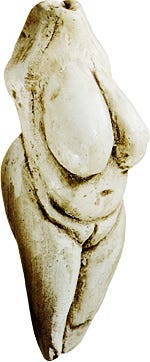

Venus of Lespugue (France). Ivory, 24–26,000 years old.

Yet if you Google the term Venus figurine or search the academic literature, you will plunge into a virtually limitless ocean of information about them: images, theses, PinterestPages, theories and speculations. Why were they made? What were they used for? More importantly, what do they mean? These are the things modern humans seem to want to know from these ancient women, who remain stubbornly resolute in their silence.

II. Ancient Races of the Ice Age

There are numerous explanations for the Venus figurines, but the one that wins by a landslide is “fertility idol.” This has always irked me for a simple reason: Upper Paleolithic people, like people over the course of 99% of human history, were hunter-gatherers. If ethnographic evidence is any clue, having lots of children is not exactly a priority for hunter-gatherers: always on the move in search of food, not only do they carry everything they own, but they carry their infants and toddlers everywhere, too. To avoid the prospect of infanticide or starvation, this means that babies are relatively few and far between; it’s not until the Neolithic (the invention of agriculture) about 10,000 years ago when big, sedentary families with lots of children becomes both feasible and desirable. Thus we have at least some reasons to think that the fertility idol hypothesis might be specious reasoning.

But before they were fertility idols, there was another interpretation, one considerably more pernicious. While Édouard Piette was somewhat ahead of his time as an archaeologist and methodical excavator, he was also a product of 19th century attitudes towards race and the “primitive” nature of tribes that were being documented during the course of the Western colonization of the non-Western world. Scientists at the time, Piette included, believed that many isolated groups such as the Khoisan people of southern Africa, were living examples of races that were “less evolved” than Europeans.

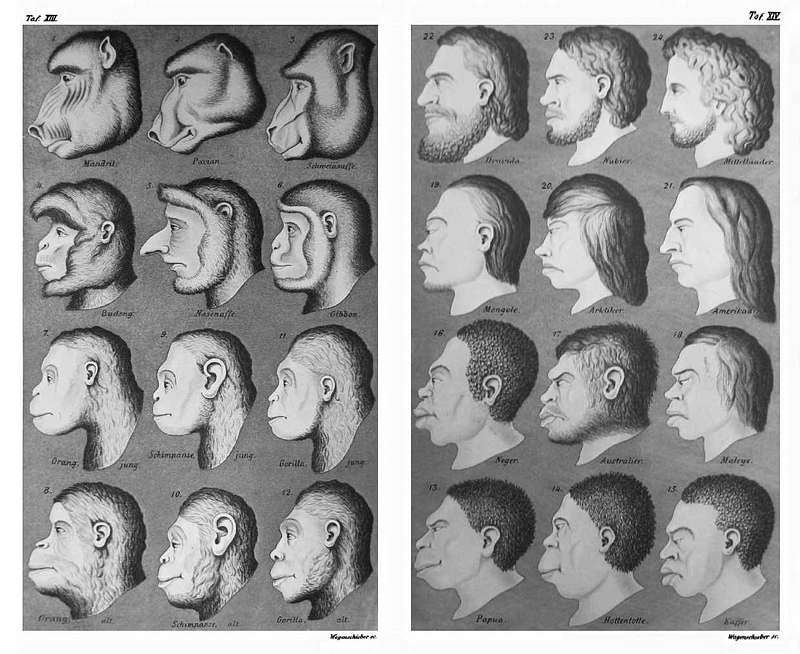

Depictions of ‘anthropoid races’ from Ernst Haeckel’s 1870 book “

Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte” (The History of Creation). Haeckel was one of the preeminent biologists of the second half of the 19th century, whose ideas at the time were as influential as those of his English counterpart, Charles Darwin. Europeans are depicted at the top right.

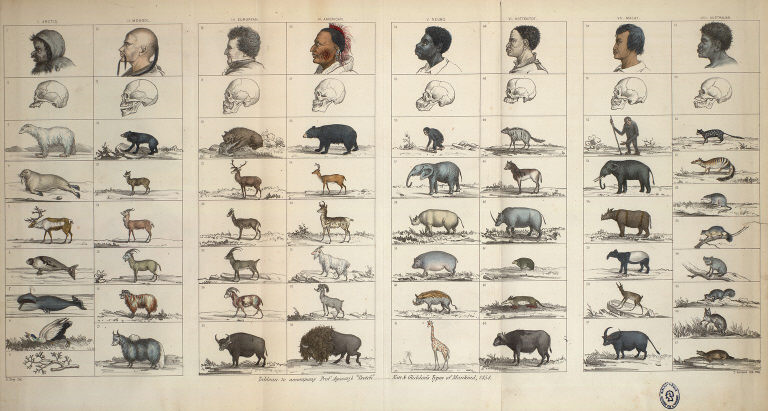

An early example of a pseudo-systematic ‘typology of race’ from “Types of Mankind” by Physician

Josiah Nott and Egyptologist George Glidden (1854). Top row of ‘races’ left to right: Arctic, Mongol, European, American, Negro, Hottentot, Malay, Aboriginal.

We know now that this idea doesn’t make sense for many reasons. Primarily, if life on Earth is constantly evolving, it’s difficult to say anything is “more evolved.” Our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees, with whom we share 98% of our DNA, a suite of cultural behaviors, and a common ancestor six million years ago, are not a “less evolved” version of a modern human. Chimpanzees (or proto-chimpanzees) continued to evolve and develop their own unique evolutionary history during that entire six million years — it just didn’t lead to traffic jams and the atomic bomb. Specific traits may be more derived or less derived (i.e. more or less recent), but the idea of “more evolved” or “less evolved” is based on the fallacy that evolutionary progress can be made. But there is no teleological ladder towards increasing biological perfection — while there is a lot of evolutionary change, any “progress” is subjective. Homo sapiens may feel we’ve made a lot of progress (the Higgs boson!), but I bet the other 8.7 million species on Earth would disagree.

A second, much more salient reason is that we now have unequivocal evidence there is much greater genetic variation within a given human population (e.g. among only Caucasians) than between two populations, illustrating that race is a social concept, not a scientific one. But in 1890, biological anthropology and genetics were in their infancy, and Piette was operating under a different rationale. Given the racially charged colonial and scientific atmosphere, it’s not so strange that Piette might conclude that the different styles of the Venus figurines were of depictions of “less evolved” prehistoric races.

Throughout the 1890s, Piette continued to unearth Upper Paleolithic figurines that he described to the public as profoundly realistic depictions of at least two distinct races that had lived in Ice Age France. The first, modeled after the Dame à la Capuche and theVénus impudique, was a much more recent and refined race, most likely Egyptian according to Piette. They had slender, hairless bodies, and were more “civilized.”

The second race represented by the Brassempouy figurines was as “hairy as Esau.” The women were large and wide-hipped. Piette describes them as “steatopygous”, meaning they possessed fatty protuberances similar to calves on the front of their thighs and buttocks, descending abdomens, and prominently displayed genitalia. Piette becomes convinced that the second group of figurines are anatomically accurate portraits of bodies similar to Khoisan hunter-gathers, referred to by Europeans as “Hottentots”, then considered by scientists to be a deeply ancient, unchanged race and thus a good analogy for Paleolithic groups. Over the course of the next few years, Piette went on to purchase other prehistoric Venuses cropping up across Europe. By the turn of century, he owned nearly every Upper Paleolithic female statuette that had been discovered to date, and virtually controlled their interpretation.

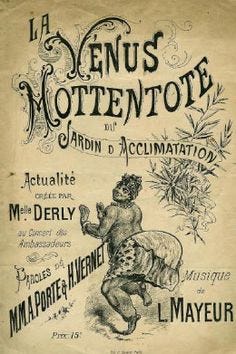

French handbill for the “Hottentot Venus”, 1810–1816

Piette was also no doubt acquainted with Sarah Baartman, known popularly as the Hottentot Venus, a Khoisan woman from southern Africa who had garnered widespread notoriety in Europe. After being orphaned and subsequently enslaved by Dutch farmers near Cape Town, Sarah (or Saartjie) was one of a number of Khoisan individuals taken to Europe and exhibited in pubic spectacles and freak shows during the early part of the 19th century. In 1810, Sarah was shipped to London and paraded before crowds obsessed by her body and perceived racial differences. Trapped in some sort of Dickensian nightmare, it goes from bad to worse for Sarah: after converting (or being converted) to Christianity, she’s sold to a Frenchman and continues to be the object of scientific scrutiny in France. Descending into alcoholism and forced into prostitution to survive, she died in 1815 of a disease of urbanity that her body likely had little resistance to. In keeping with her general inhumane treatment during her Grand Tour, she was then dissected by famous naturalist George Cuvier, who was curious about her steatopygous buttocks and descending labia, crudely referred to as the “Hottentot skirt.” Cuvier then made molded wax casts of Baartman’s genitalia (which were preserved in formaldehyde and sat next to the preserved brain of French anthropologist Paul Broca) that were on continuous display in museums in France up until the 1970s. Baartman’s remains were finally repatriated to South Africa and buried in 2002, nearly two-hundred years after her enslavement, showcasing, and tragic end.

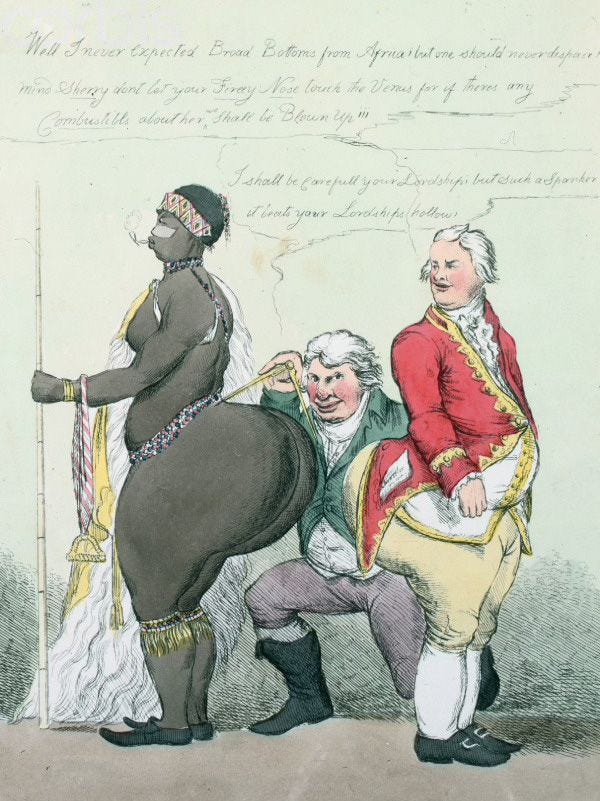

Caricature of Saartje Baartman, England 1810–1816.

In his article “The Women of Brassempouy” (to which this essay is heavily indebted) NYU anthropologist and expert on Paleolithic art Randall White makes a strong case that Piette’s use of the term “Venus“ ”figurines was less a comparison to Greek statuary than it was ironic and derisive: “Venus” was not meant to compare the Paleolithic statuettes to the classically beautiful Venus de Milo, but to highlight their similarity to what some Europeans viewed as the grotesque or primitive anatomy of the Khoisan and other groups they were colonizing. Thus, the Venus figurine narrative at least in part began as kind of a cruel anthropological joke referring to a woman whose life and dignity were stripped away from her ostensibly for the advancement of science, but effectively for entertainment value.

To add insult to injury, the name stuck. Shortly following Piette’s discoveries, every Paleolithic figurine bearing even the most remote resemblance to the female form was referred to as Venus.

III: A Religion of Magical Homeopathies

Within a few decades, however, race soon gave way to an unrelated interpretation of the figurines: they were…magic! At the time, anthropologists were often preoccupied with documenting the magical practices among people they considered. They viewed tribal magic as an important animistic or totemic precursor to civilized, monotheistic Western religions. Particularly important among primitive groups was the use of “sympathetic magic,” a practice that relied upon something Ur-anthropologist and mythologist James Frazer called the Law of Homeopathies: the physical similarities between two objects, no matter how seemingly small, link them together. This relationship can then be manipulated by the magical practitioner. It’s essentially the principle behind homeopathic medicine. It’s also part of the magic of the voodoo doll: you wish to remotely affect some sort of change, malevolent or benevolent, upon an individual. You create a likeness of the individual. And then you exact whatever revenge or restoration you have in mind upon the likeness, thus precipitating similar results in the real world.

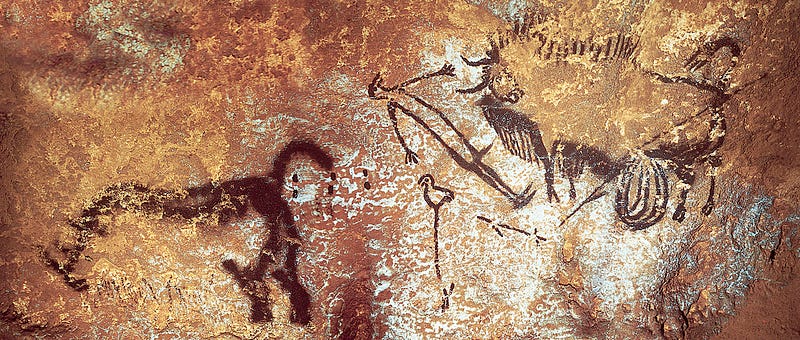

Archaeologists were soon to pick up on sympathetic magic as an extremely useful explanatory tool for all sorts of questions they had about the distant past. Why did a Paleolithic artist draw a bison with a spear through its neck on a cave wall? So that he might more effectively kill the bison in the real world. It’s much easier to deal the disconcerting prospect of coming face to face with a severely pissed off ten ton woolly mammoth if you’ve already killed the leviathan in your mind and on the wall of the cave first.

Paleolithic cave painting of a bird-headed man, a wounded, disemboweled bison, and rhinoceros typically interpreted as sympathetic hunting magic. Lascaux Cave (France). ca. 15,000 years old.

In France, the mantle of archaeological preeminence had passed from Piette to a very different character: Henri Breuil, a French ethnologist, archaeologist, geologist, and soon-to-be the world’s foremost expert on Paleolithic art. Abbé Breuil, as he was known, was also a Catholic priest. So perhaps it is no surprise that sympathetic magic, essentially a form of primitive religion, should have appealed to him as an explanatory framework for Paleolithic art.

Abbe Breuil, the “Pope of Prehistory.”

(France).

Like Piette, Breuil had been looking for an alternative to the dominant l’art pour l’art’ (“art for art’s sake”) paradigm widely used by art historians at the time to explain ancient art. Breuil realized that this was an exceedingly Modernist approach to understanding Ice Age art, and that it didn’t really explain the types of figures he was seeing at Paleolithic sites across Europe. For him, the nascent artistic abilities of Paleolithic artists went hand in hand with the development of religious beliefs meant to explain the complex links between the physical and non-physical world. The Venus figurines, too, were a form of sympathetic magic: reproductive magic depicting pregnant or otherwise fecund-looking women to promote healthy fertility among Paleolithic people. After decades drawing and cataloging Paleolithic art, by the 1950’s, Breuil had become the key figure — the gatekeeper — in the study and interpretation of Ice Age art, his theories so influential that they persist in one guise or another to this day.

IV. The Raw and the Cooked

It wasn’t long before people began to question the ideas of the Pope of Prehistory (Breuil’s playful sobriquiet). Many archaeologists resented his fame and power, his colorful but not-fantastically accurate stories recounting the history of certain well-known pieces of Paleolithic art, and his sloppy (by modern standards) and inaccurate renderings of cave paintings.

Nevertheless serious challenge to the sympathetic magic hypothesis came not from within the discipline, but from philosophical quarters. Under the auspices of immensely influential scholars such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, by mid-century French Structuralism had taken fire in anthropological theory.

Anthropologist and philosopher

.

As with all ideas that impact anthropology, the influence of structuralism trickled down into archaeological circles more slowly, but within a short time, it had a tremendous impact on the way Paleolithic art was interpreted. Since more ink has been spilled on structuralism than just about any other philosophical topic in the past fifty years, any attempt to sum it up a single sentence is bound to be, in one way or another, a complete failure. However, in a courageous attempt to embrace what I have come to recognize as life’s seemingly limitless supply of failures, I will give it a shot: structuralism is, at its heart, a recognition that all human concepts — every trope, word, or idea, however fleeting — are relational. Concepts cannot be understood in an atomized fashion, but rather their meaning derives from their relationship to other ideas or concepts; therefore no element of a culture can be understood on its own, but only as part of a web of interrelated meanings. Certain concepts are fundamental, and form the basis of more complicated ones. Male cannot as a concept meaningfully stand alone, but rather must be understood in the presence of its antithesis, female. And because these types of dyads are foundational to the way all humans think, they are also universal, predictably the same from culture to culture. Theoretically it’s a bit more complicated than this, but not radically so. Emerging from the work of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, structuralism had clear implications for anthropology and linguistics, but its application to archaeology was a bit more curious. French archaeologists during this period, most notably Annette Laming-Emperaire and André Leroi-Gourhan (the French archaeological heir to Piette and Breuil. As a member of the French resistance, Leroi-Gourhan was in charge of hiding the Venus de Milo after its evacuation from the Louvre to protect it from the plundering Nazi Kunstschutz), took an almost literal approach to applying structuralist principles to Paleolithic art, mapping complex and specific cultural ideologies onto the physical layout of cave art. According to Leroi-Gourhan, “All signs in caves are substitutes for human sexual representations.”

The deep recesses of the caves were equated with qualities associated with women (cold, wet, dark, nature), the binary opposites of qualities the structuralists equated with men (hot, dry, light, culture). And if men were the purveyors of culture, women must then be the reproducers of nature. Thus, even with a fancy new critical theory, the Venus figurines were for all intents and purposes still basically fertility dolls. One step forward, two steps back.

V. Honest to Goddess

And then, interpretively speaking, something very important happened in terms of how the Venuses were understood: the women arrived — specifically, a short, spunky, and brilliant woman from Vilnius named Marija Birutė Alseikaitė, better known to the rest of the world as Marija Gimbutas, the mother of the Mother Goddess movement. From the start, Gimbutas’ intellectual pedigree was a strong one: her mother was the first female physician in Lithuania, and in 1918 her parents founded the first hospital in Vilnius, a city that was at the time enjoying a brief respite after WWI before being torn apart again by Hitler and Stalin. She grew up surrounded by artists and musicians and writers, a little girl steeped in Lithuanian folklore. On her father’s deathbed, Gimbutas promised him that she would become a scholar. But what to study?

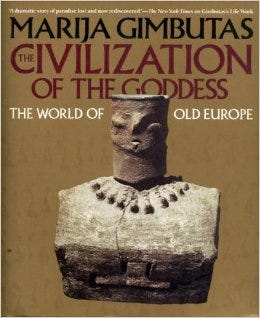

After fleeing from city to city with her husband and baby daughter to escape alternately the Nazis and the Soviets, Gimbutas eventually earned a doctorate in archaeology in Germany after the war and landed at Harvard in the 1950s. There she began a prolific career that fused linguistics, ethnology, and archaeology to challenge traditional assumptions about Europe’s prehistory. Always something of an iconoclast, it wasn’t until the mid-seventies that Gimbutas unleashed a theory which would fundamentally change the public’s conception of women in the past in a series of popular books with titles like The Language of the Goddess or The Civilization of the Goddess that sold millions of copies. In these books, she laid out an alternate history of Europe and the Old World, one in which prehistoric groups were led more or less by peaceful, egalitarian women who focused on worshiping the regenerative powers of the Mother Goddess.

Cover of Gimbutas’ Th

e Civilization of the Goddess (

1991)

Gimbutas worked to popularize the notion that the European female figurines were less fertility dolls than they were fertility deities. In her “Kurgan Hypothesis” (there can be only one…Kurgan Hypothesis) she suggested that waves of blood-thirsty horsemen from the Eurasian steppe invaded these gentle, gynocentric societies, bringing with them not only Indo-European — the root tongue of the languages now spoken by 3 billion people — but also militarism, social inequality, and their associated social ills. Matriarchy gave way to patriarchy; warriors replaced peacemakers. Among the moments in the human career, it was not a particularly bright one.

Except that it didn’t really happen that way, or at least that’s what a lot of archaeologists contend. Critics of Gimbutas’ archaeomythological approach suggested there was little hard evidence to justify her interpretive leaps about a pervasive Goddess culture. (The oldest European Paleolithic art is now thought to be a red disk and outlines of human hands in Northern Spain, but thus far no one’s suggested Ice Age sun or hand-worshiping cults). In any case, despite a six decade career devoted to unraveling the mysteries of the past, Gimbutas received somewhat of a critical lambasting and, like many other successful but decidedly old school archaeologists before her, saw some of her less controversial ideas too easily written off, partly because of shelf-date and partly because of mean-spirited professional jealousy.

Setting aside the veracity of her claims, what is more interesting is why the Goddess idea seemed so phenomenally attractive in the mid-1970s. Second-wave feminism and the sexual revolution had just begun to be fully digested by the public. Gimbutus, who claimed to be surprised that feminists were interested in her ideas, had unwittingly tapped straight into the zeitgeist. Her ideas about Goddess worshippers as peaceful stewards of the Earth also dovetailed nicely with the simultaneous rise of ecofeminism (which related the devaluation of women to that of the environment) and the culture’s generalized anti-war anxiety resulting from the war in Vietnam. For a brief moment, Gimbutas provided the archaeological credibility for modern day Goddess worshipers looking to the past for the same reason that all humans look to the past: for a sense of continuity, an answer to the question “How did we end up here?”

VI. Paleoporn

The strange thing about the history of the Venus figurines is that every time you would think that a weirder, more chronologically ethnocentric interpretation couldn’t possibly come along, it invariably does. “Paleoporn” is the term applied facetiously by anthropologists to explanations of largely unclothed Paleolithic women as explicitly sexual or erotic in nature: as one male scholar put it, “diluvial plastic pornography” —objectified fantasies made by men for men (and, of course, adolescent boys).

Illustrations from Guthrie and Kurtén’s work.

Its most vocal proponents tended not to be anthropologists but rather paleontologists such as Björn Kurtén and R. Dale Guthrie, men who had been seduced by the mysteries of European Paleolithic art in the course of documenting extinct animals of the Ice Age. In his magnum opus The Nature of Paleolithic Art, Guthrie makes the case for biological explanations for both the profound naturalism of Paleolithic artists, and their repetitive depiction of certain parts of the female anatomy and emphasis on sexual imagery.

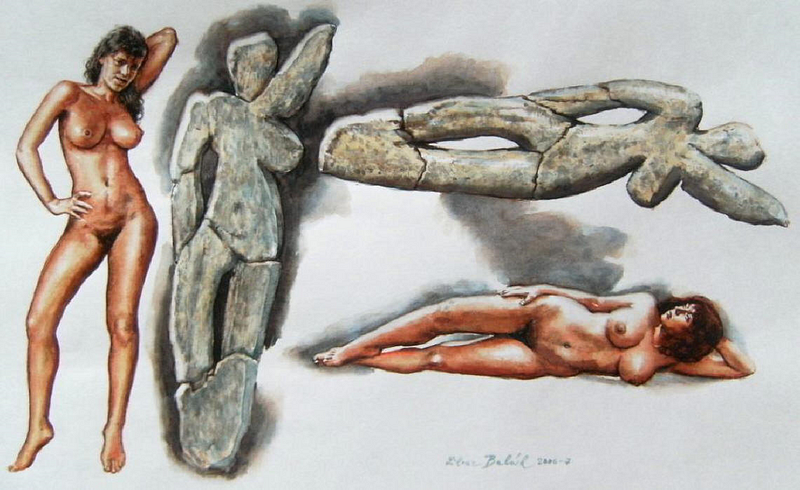

With chapter titles like “Testosterone Events and Paleolithic Imagery” and “Full-Figured Women — In Ivory and in Life” Guthrie paints a picture of horny Paleolithic teenagers awash with hormones, away from the watchful eyes of adults, fabricating their sexual fantasies at the back of the cave by torchlight and otherwise engaging in lots of dumb, risky behaviors that tend to get them hurt. Depicting full-figured, curvaceous women in gently submissive poses they found particularly erotic, lying down suggestively or bent over from behind like Paleolithic pin-up girls, Kurtén and Guthrie’s Ice Age artists have sexual tastes best described as very late ’70s Playboy magazine.

Artistic interpretations of the Upper Paleolithic Venus figurines in strikingly modern sexually-suggestive poses, following the work of Guthrie.

When the wide-hipped women are depicted with partial clothing or jewelry on, it is to emphasize their partial nudity, rather than, for instance, to convey information about fabric or personal ornaments. According to Guthrie, the paleolithic artists tended to emphasize parts of the body they found erotic, centering in on the torso, and deemphasized the parts of women’s bodies they find less erogenous — their feet and faces. Phallic-looking figurines carvings may have functioned as “Paleolithic dildos”, according to Guthrie. Because, if modern men are obsessed with pornography, why would it be any different for Paleolithic men?

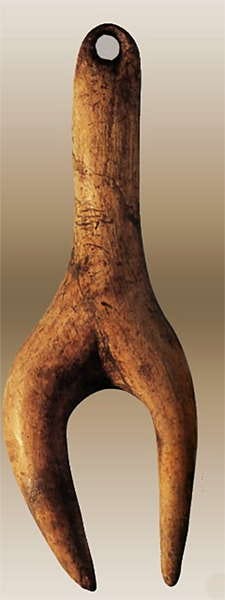

Artistic interpretation of the Venus of Engen.

Unsurprisingly, a number scholars, particularly feminist archaeologists, have taken androcentric or disproportionately sexualized interpretations of Paleolithic art to task. On the most basic level, several note that only about half of the “Venuses” are demonstrably female in the first place. Figurines described as “rods with breasts” more closely resemble a penis and testicles when turned upside down; many figurines are so abstract it’s difficult to call them human in the first place.

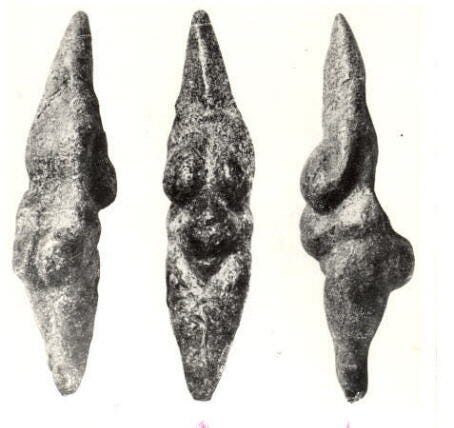

Dolní Věstonice “Venus figurine” (Venus XIII). Ivory pendant, 25–29,000 years old.

The Paleoporn narrative also lacks any discernible female perspective, and falsely equates nudity with seduction and eroticism: in reality, we haven’t a clue about Paleolithic conceptions of gender and sexuality. It is a narrative that, similar to mainstream pornography, takes the objectification of women as a given. And what about those strikingly modern pin-up poses? Racy stuff. Who was the Paleolithic Hef behind all of this?

One of the most insightful critiques of this overly sexualized interpretation of the Venus figurines came from University of Denver archaeologist Sarah Nelson, who examined the types of language invoked in the Venus literature by tallying the re-occurrence of specific words. Highest on the list were: “breasts,” “sexual,” and (of course) “fertility.” For feminist archaeologists such as Nelson and Cynthia Eller, ideas of the Venuses as the sexy women of the past, or the reproducers of nature, or ancient Goddesses are all modern mythologies we have created for ourselves, for our own purposes. We see what we want to see.

VII. From Paleoportraits to Performance Art

One benefit of an archaeology informed by third wave feminism has been not only to challenge chauvinistic interpretations of Paleolithic life and art, but to question and to deconstruct the binary distinctions — male vs. female, culture vs. nature, hunting vs. reproduction — that structured the debate surrounding its meaning for over a century. Less burdened with false dichotomies and historical baggage, new avenues of scientific inquiry have begun to provide glimpses into the world of the Venuses. Might they have been Paleolithic toys, lost in the dark recesses of the cave? Depictions of the female body during pregnancy perhaps used for teaching? Self-portraits from the perspective of looking at one’s own body?

Drawing parallels to the metabolism of hunter-gatherers similar to those of the Paleolithic, one scholar thinks he may have solved the riddle of the Venuses: in his words, “They were fat!” According to Dr. Erik Trinkaus, a physical anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis and an expert on our Neandertal cousins, the best explanation for this “Adiposity Paradox” — i.e. the paradox of how the Venus makers would have been familiar with obesity considering their generally fit hunting and gathering lifestyle — is a combination of artistic license, periodic sedentism, and high caloric intake. Among people accustomed to being on the move and occasionally facing starvation, bouts of sitting around and eating could have lead to rapid weight gain among some, perhaps thusly depicted in the Venuses. Like the Rubenesque women of 17th century painting, being well-fed may have been essentially a type of status symbol.

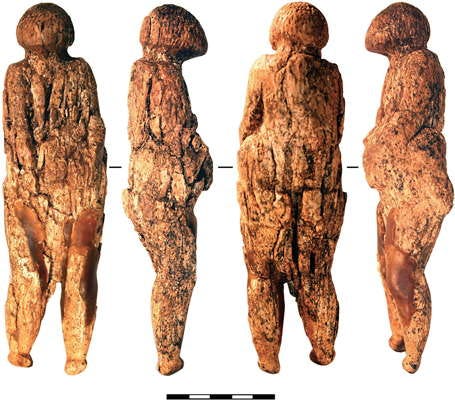

Other anthropologists look not to the bodies of the Venuses, but to what they are wearing. Professor of archaeology Olga Soffer has pointed out the sophisticated weaving patterns of the hats, hoods, and bandeaux worn by the Venus of Willendorf, the Venuses of Kostenki, La Dame à la Capuche, and others.

Venus of Kostenki (Russia) illustrating woven clothing. Ivory, 22,000 years old.

Artist’s depiction of the woven cap worn by the Venus of Willendorf.

Depictions of this technology could have been a sort of blue print or instruction manual, simultaneously underscoring a particular status or cultural capital enjoyed by at least some Paleolithic women. Soffer also sees a performative aspect in Paleolithic art, as some of the clay figurines show evidence of being thrown into a fire while still wet, causing them to explode violently.

Because of the diversity of different styles and types of Venuses, it’s now generally accepted that not only is the name misleading, but so is the idea that these unique objects belong to a single cultural tradition or idea in any meaningful sense. The future of the term rests only in its convenience.

VIII. In the Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Although the idea really upsets a lot of archaeologists, unless you are an exotic quantum particle or an exception to the second law of thermodynamics, the past, especially the deep past, isn’t “out there” for you in any meaningful sense any more than the events that have transpired in your life are “out there” for you to re-experience: for all intents and purposes, the past for humans is a narrative, a certain type of memory. There are physical fragments of it which can be counted, categorized, and read for signs of significance, but little more. This is made more poignant by the fact that we are often obsessed with the past, spending large parts of our lives thinking about it, swimming down different streams of memory.

While it is clear the Venuses are symbols of something, what they are symbols of we will never know: unlike stone tools, symbolism doesn’t preserve very well in the ground, or in the back of the cave, or anywhere else for that matter. Produced by minds as cognitively sophisticated as our own, the Venus figurines are no more interpretativly available to us than Les Demoiselles d’Avignon would be to a Paleolithic person who stumbled across it.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,

Pablo Picasso. Oil on canvas, 1907.

As both archaeologist Sarah Nelson and writer Jack Hitt note, the modern concept of the deep past is really a mixture of scientifically-derived facts, contesting scientific interpretations, and cultural consensus: a collective mythology we sometimes choose to believe in that serves our present needs nearly as much as it serves the objective truth. What you get when examine the Venus figurines in depth is not so much a glimpse into life 30,000 years ago, but a crash course in the history of anthropology, and in epistemology: how we know what we know, how we construct meaning out of knowledge and experience. To trace the history of the Venuses is to realize that “zeitgeist matters”: interpretations of the past are very much inseparable from the time period and context in which they take place, staggering under the weight of the palimpsest of previous interpretations.

In his documentary about Paleolithic art Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Werner Herzog inserts a scene from the 1936 film Swing Time in which Fred Astaire is shown dancing with his shadows. As he comes to a halt, the shadows break free of Astaire, and continue to dance of their own accord. The Venuses are like these shadows: they have broken free from their original creators and structures of signification, and have taken on a life unto themselves. Ask them as many questions as you like, but don’t expect any answers. Like little Mona Lisas, they know their allure rests in keeping their secrets.

******************************************************************

Berekhat Ram ‘Venus’ (Israel). Red tufic stone, age unknown.

Venus of Brassempouy (France). Ivory, 25,000 years old.

Venus of Dolní Věstonice (Czeck Republic). Ceramic, 25–29,000 years old.

Venus of Engen (Germany). Jet (lignite), 15,000 years old.

Venus Flytrap (WKRP in Cincinati)

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AwzaifhSw2c[/embed]

Venus in Furs, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch. 1870.

Venus of Galgenberg (Austria). Serpentine, 30,000 years old.

Venus of Garagino (Ukraine). Ivory, 22,000 years old.

Venuses of Gönnersdorf (Germany). Ivory/bone/antler, 11,500–15,000 years old.

Venus of Grimald (Italy). Steatite, 25,000 years old.

Venus of Hohle Fels (Germany). Ivory, 35–40,000 years old.

La Vénus impudique

(the immodest Venus) (France). Ivory, 16,000 years old.

Venus of Laussel (France). Limestone bas-relief, 25,000 years old.

Venus of Lespugue (France). Ivory, 24–26,000 years old.

Venus of Kostenki (Russia). Ivory, 22,000 years old.

Venus of Mal’ta (Russia). Ivory, 20,000 years old.

Venus de Milo (Greece). Marble, 2,100 years old.

Venus with a Mirror, Titian. Oil, 1555.

Venus of Monruz (Switzerland). Jet (lignite), 11,000 years old.

Venus of Moravany (Slovakia). Ivory, 23,000 years old.

Venus of Parabita (Italy). Bone, 17,000 years old.

Venus of Petřkovice (Czech Republic). Stone, (Gravettian, 23,000 years old)

The Venus of Polichinelle, carved in green steatite, length 61 mm, 27 000 years old, found at Grimaldi.

Gillette Venus razor (“Get Your Goddess Showing!”)

Venus of Renancourt (France). Chalk, 23,000 years old.

Venus el Rombo, or the Lozenge Venus (Italy). Green steatite, 25,000 years old.

Venus of Savignano (Italy). Green serpentine, Upper Paleolithic.

Venus of Willendorf (Germany). Limestone and red orchre, 25–28,000 years old.

Venus Williams (Tennis player).

Venus of Zaraysk (Russia). Ivory, 20,000 years old.

*****************************************************************